Consensus Decision Making at the Commons at Windekind

Overview and current policy

“So, open your mouth, lad! For every voice counts!” Dr Seuss

The Quakers hold a firm commitment to the common humanity of us all and our ability to decide together. At the heart of consensus is a respectful dialogue between equals in which there is active participation and the sharing of power equally. This makes it a powerful tool for empowering individuals but also for bringing people together around common goals and then, because of Unanimity, getting things done. Consensus making flourishes in an environment, that fosters respect for the individual, trust, cooperation and mutual support to achieve agreeable solutions and outcomes. Once agreed upon, these decisions, because individuals have invested in process of creating them, become vital motivators for taking actions that move the community forward.

Consensus decision making is an alternative to the commonly practiced non-collaborative decision making processes. Robert’s Rule of Order, for instance, is a process used very effectively by many organizations, including Vermont towns, like Huntington, for Town wide decision making at Town Meeting.

The goal of Robert’s Rules is to structure the debate and passage of proposals that win approval through majority vote. However, this process does not emphasize the goal of full agreement, nor does it foster whole group collaboration and the inclusion of minority concerns in resulting proposals. Critics of Robert’s Rules believe that the process can involve adversarial debate and the formation of competing factions. These dynamics may harm group member relationships and undermine the ability of a group to cooperatively implement a contentious decision.

In the case of Huntington, we have experienced, over a 50-year period, Robert’s Rules used very effectively, in part because the community wants to work together and achieve general consensus.

Consensus decision making is also an alternative to “top-down” decision making, commonly practiced in hierarchical groups. Top-down decision making occurs when leaders of a group make decisions in a way does not include the participation of all interested stakeholders. The leaders may (or may not) gather input, but they do not open the deliberation process to the whole group. Proposals are not collaboratively developed, and full agreement is not a primary objective.

Critics of top-down decision making believe the process fosters incidence of either complacency or rebellion among disempowered group members. Additionally, the resulting decisions may overlook important concerns of those directly affected. Poor group relationship dynamics and decision implementation problems often result.

Consensus decision making addresses the problems of both Robert’s Rules of Order and top-down models. The goals of the consensus process include:

- Better Decisions: Through including the input of all stakeholders the resulting proposals can best address all potential concerns.

- Better Implementation: A process that includes and respects all parties, and generates as much agreement as possible sets the stage for greater cooperation in implementing the resulting decisions.

- Better Group Relationships: A cooperative, collaborative group atmosphere fosters greater group cohesion and interpersonal connection.

The process is structured making use of several distinct roles designed to make the process run effectively. Although the name and nature of these roles varies from group to group, the most common role are the facilitator, a timekeeper, an empath and a secretary. Some decision-making bodies, in the interest of simplicity, combine the role of facilitator, timekeeper and empath into one and opt to rotate these roles through the group members in order to build the experience and skills of leadership-and fellowship- across the community.

- Facilitator: As the name implies, the role of the facilitator is to help make the process of reaching a consensus decision easier insuring participation by all members, the active examination of all points of view and alternatives in a safe and civil environment with actions and outcomes agreed upon in a timely manner.

Facilitators accept responsibility for moving through the agenda on time and ensuring the group adheres to the mutually agreed-upon mechanics of the consensus process. Some consensus groups use two co-facilitators, adopted to diffuse the perceived power of the facilitator and create a system whereby a co-facilitator can pass off facilitation duties if he or she becomes more personally engaged in a discussion or a debate.

- Timekeeper: The purpose of the timekeeper is to ensure the decision-making body keeps to the schedule set in the agenda. Effective timekeepers use a variety of techniques to ensure the meeting runs on time including: giving frequent time updates, ample warning of short time, and keeping individual speakers from taking an excessive amount of time.

- Empath : The empathy is charged with monitoring the 'emotional climate' of the meeting, taking note of the body language and other non-verbal cues of the participants. Defusing potential emotional conflicts, maintaining a climate free of intimidation and being aware of potentially destructive power dynamics, such as sexism or racism within the decision-making body.

- Secretary: The Secretary highlights the main components of the decision making process and records the decisions that are made as a manner of record for members of the Common and Public record.

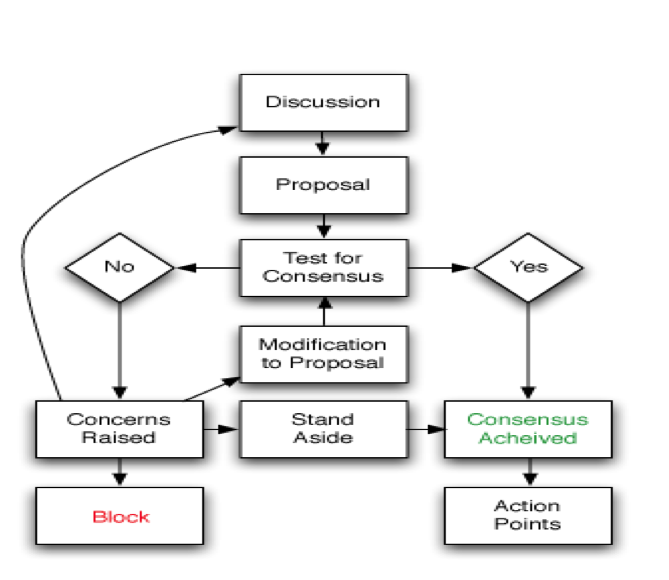

We find the above model helpful in explaining the Consensus building process. The model starts with a concern that needs to be addressed in the community, for example, establishing a budget for a new community project proposed by some members of the community. Once established in a clear manner that concern can go in several direction, the first and most simple would be that the entire community understands the proposal and supports it so they decide to stand aside and let the principles of the decision go forward. This is a rare occurrence even in a small community since people are curious and almost always have at a minimum- questions and comments.

The second path is a process in which the project is reviewed by the community, questions are raised, feedback is given and modifications are made that are acceptable to the community and therefore consensus is achieved. The third, the most complex path, is through the process of discussion in a meeting where there are multiple views that will involve more give and take and compromise in order to reach a proposal that everybody can agree on.

Conditions that Favor Unanimity

Consensus decision-making is not for everybody in every circumstance.

Unanimity needs an environment to flourish, that environment has to be created by the participants of a host Community and then sustained by an agreed upon process that has rules. Thus, it is important to consider what conditions rules make full agreement more likely.

Here are some of the most important factors that improve the chances of successfully consensus making. After each factor is a brief analysis of the various advantages or disadvantages when these factors enjoy here at Windekind.

- Small group size-Favorable in our case because we are talking about a maximum of seven families.

- Clear common purpose-Marijke and I are clear about our visions and values, which includes a very high value of honoring diversity and therefore flexibility. We believe that this clarity will attract like-minded people who self select in (or out) because they identify un-indentify with our values and goals. In addition, we have developed a screening process in our By-Laws that allows the community and perspective members to test for acceptable levels of commonality of purpose and goals while honoring diversity.

- High levels of trust-Our experience is that trust thrives under conditions in which people are clear, reliable predictable honest and expansive/engaging with one another. Fun and humor are often good indicators of trust and respect augmented by the willingness to apologize and the ability let go of rigid held convictions. Conversely trust declines and even disappears in environments of blame confusion and judgment,

We expect that the Common, given its participatory nature, will attract people who trust themselves and therefore others, they will work hard to foster a climate of greater trust and mutual respect while realizing that a climate of trust is always a challenging goal in any community. One group that we have been successful in gaining a high level trust with is our guest, we trust them with payments and in other areas and likewise they trust us. (See our Trip Advisor reviews)

- Participants well trained in consensus process. Consensus making requires a good understanding and agreement of the mechanics of the process and its underlying assumptions. Many of these are skills and knowledge’s are gained through experience but sometimes-focused workshops, on an as needed basis, are very helpful.

- Participants willing to put the best interest of the group before their own. We are interested at Windekind in creating an all boats raise on a rising tide effect meaning the best interest of the individual is achieved when the best interest of the community as a whole is realized. This requires trust and sometimes a suspension of self-interest in light of the greater community interest. Over the years we have experienced considerable success (also failure) in this area with the town, our neighbors, members of our family, the ski center and our personal friends and the farm’s guests.

- Participants willing to spend sufficient time in meetings. I am fond of Winston Churchill quote “Democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the others.” A lifetime of experience with many forms of democratic and consensus making has taught us again and again about the time and effort required but at the end of the day when decisions are made and put into place the results have been considerable.

The best personal example I can think of is my long career with developing planning and regulations in Huntington. There were so many instances in which it seemed that we were proceeding at less then snail speed, but now as I look back at this work the tangible achievements for our community have been remarkable. Although these Boards do not operate on a strict consensus model there are very few decisions made without the broad based consent of the group. Humor, a sense of fun and well-prepared participants make the process more interesting and enjoyable.

- Skillful facilitation and agenda preparation. Yes!